Rural 2.0: Reinventing smallholders

The quality of a moderately prosperous society and socialist modernisation is determined by agricultural competitiveness, rural environment and rural incomes.

President Xi Jin-Ping

Agriculture in China

The Household Responsibility System

In China, the household responsibility system (HRS) was launched after the people’s commune system was abolished in the early 1980s. It redistributed land to farmers in the form of contracts and agricultural production operation was returned to individual households. The HRS has encouraged a wide range of farmers to expand production and promoted rural development.

But organising smallholder farmers and integrating them with the modern value chain remains challenging. Over 227 million smallholder households in China cultivate a total of 120 million hectares of farmland and produce over 20% of the world’s food, though average land size per household is less than 0.3 hectares.

Recent Structural Reforms

In 2017, China pledged to pursue a rural revitalisation strategy to prioritise the development of its agriculture and rural areas and build a “moderately prosperous society” by eradicating extreme poverty by 2020.

China’s rural revitalisation strategy signaled a shift in the country’s development focus from unbridled economic growth to better quality expansion and improved wealth distribution.

A majority of smallholder farmers operate in a fractured value chain that prevents them from benefitting from the investments being made into the agricultural sector.

The Problem: A fragmented ecosystem of smallholder farmers, market, and technology

1. Fragmented value chain

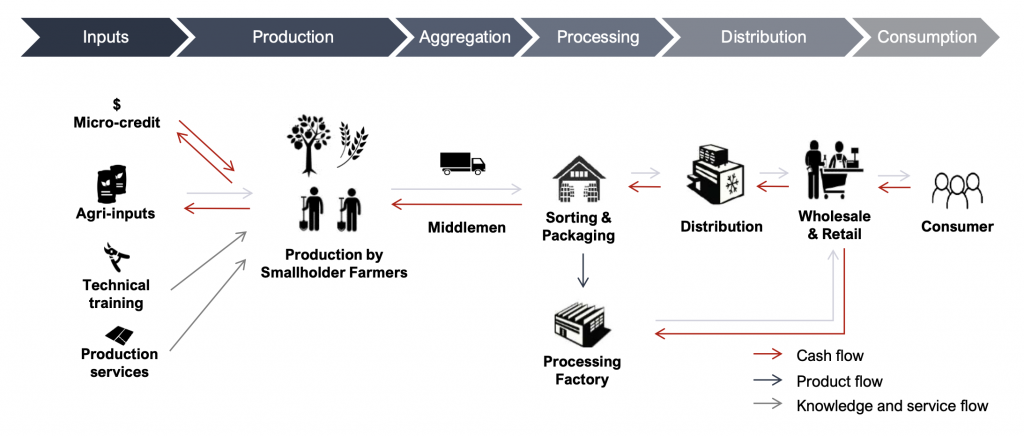

Majority of produce in China are grown by smallholder farmers and sold through middlemen via a long and fragmented value chain. They have no control of the produce once it is sold to the middlemen or in the sorting / packaging process. A bulk of the value is made from the middlemen level onwards up to retail as paid by the consumer. Also, due to the unorganised nature of the value chain, it is difficult to address quality and sustainability issues in production and implement a fully traceable and verifiable system.

2. Lack of Organisation strategies

- Lack of farmer organisation: inability to achieve the scale needed for effective service provision, particularly when consolidating land for running large machinery for field crops

- Lack of professional talent: there is a not enough technical or management talent to run organisations effectively, as many younger professionals have left for the city.

- Lack of trust from farmers: farmers have little-to-no loyalty towards a particular service provider.

- Lack of professional training for companies: founders or people running the company may lack professional skills and support needed to run accounts, manage teams and farmers

Transformation: Achieve Scale, Leverage Technologies

1. Building a supply chain

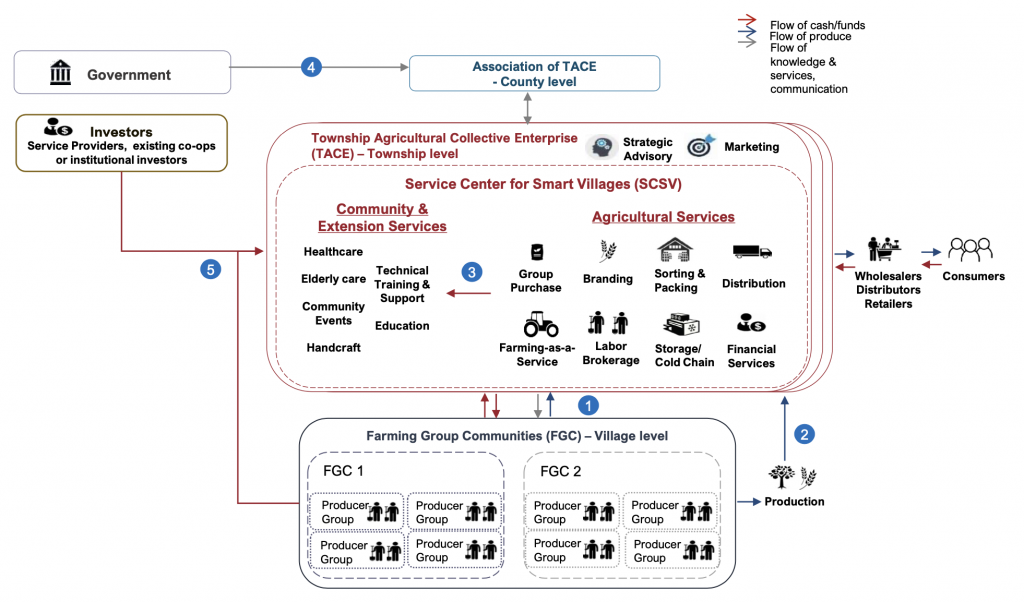

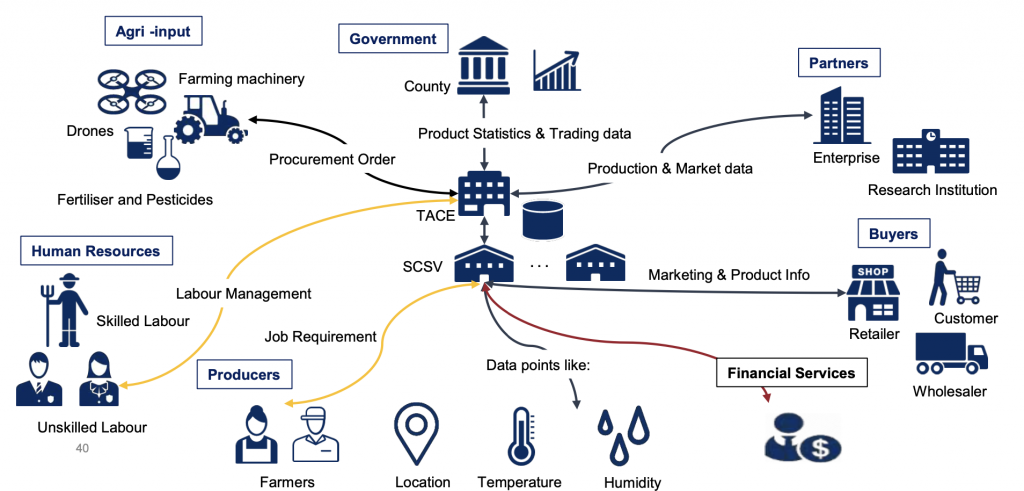

A Township Agricultural Collective Enterprise (TACE) is established to provide services via a Service Centre for Smart Villages (Service Centre or SCSV for short) at each town.

TACE will organise farmers in the township to gain economies of scale and provide services through the Service Centre that will generate a profit as well as create higher returns for farmers. Key services include group purchase of agri-inputs, post-harvest sorting, packaging and branding, labour brokerage, financial services, and “Farming-as-a-Service”. The SCSV serves as a platform for agricultural service providers to provide services to members at scale through a more efficient and cost-effective manner.

The Association of TACE at the county-level then connects the TACE at each township to ensure resources are coordinated and external stakeholders like the government are managed. It is also in charge of creating standards for product and traceability system standards. Investors, whether institutional or existing service providers, will provide funding and act as business partners for TACE.

2. Crop fields organisation

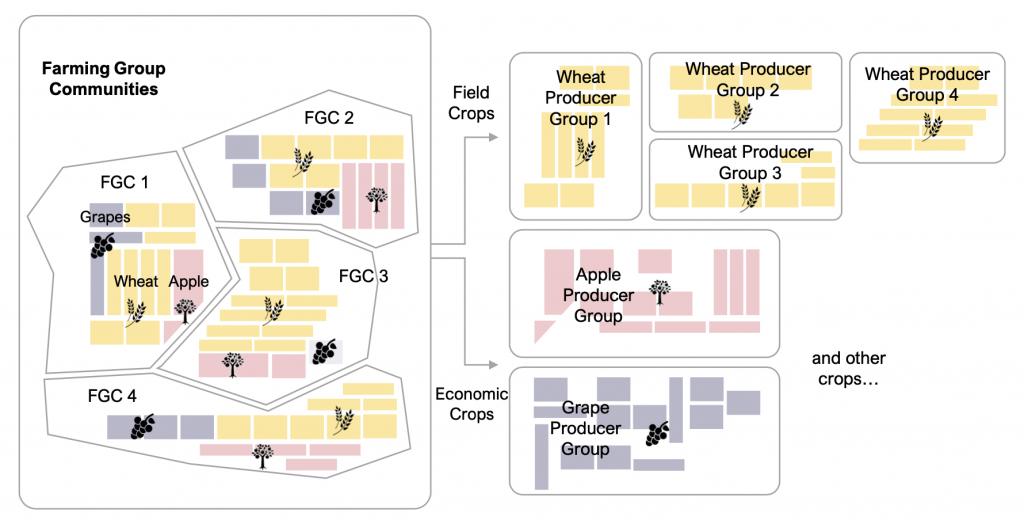

Each Producer Group (PG) conducts its own economic activities based on the type of crop they grow (e.g. grapes, apples, peaches and field crops etc.). This division is due to the different conditions for each type of crop, particularly between field crops and economic crops. Each Producer Group will aggregate demand for training and services to work directly with the SCSV.

However, Producer Groups are limited by geographical proximity, so various PGs are then grouped into FGCs by location for easier management. Each FGC will have a self-elected leader for better management and communication with TACE.

Scale is achieved when farmers are organised into Farming Group Communities (FGC). Each FGC consists of different Producer Groups (PG) that grow the same type of crop and are within geographical proximity of each other. Farmer-members of TACE will become owners of the organisation through an initial investment, and will have voting rights as well as be part of a shared profit scheme.

3. Leverage Scale to Develop Technological Advantage

Digital technology can help create higher value for farmer produce, through information sharing and service provision.

Currently, market information is inaccessible to farmers, which limits their ability to capture value. Vice versa, consumers have increased concerns about food safety and sustainability, yet know very little about what happens in the production stage.

TACE will develop a digital application that:

- Provides Producer Groups access to market information, trends and intelligence that can support management decisions, planning and negotiations with buyers.

- Improves traceability of products by tracking data from inputs, production, sorting, logistics and sales. Traceability not only improves consumer confidence and supports branding, it is also a risk-management tool which allows businesses to recall products identified as unsafe.

- Provides a platform for labour management and sourcing for Producer Groups.

- Provide a platform for transaction of financial services like loans and crop insurance.

Data throughout the value chain can be shared via the digital application, with an emphasis on production data (agri-input orders, production data points like location, temperature, humidity etc., and storage/logistics information). The platform can also be used to share market information and labour information to facilitate other services offered by the SCSV. With this centralised data, the TACE team will be able to unlock new insights and patterns throughout the value chain, leading to better and more efficient operations.

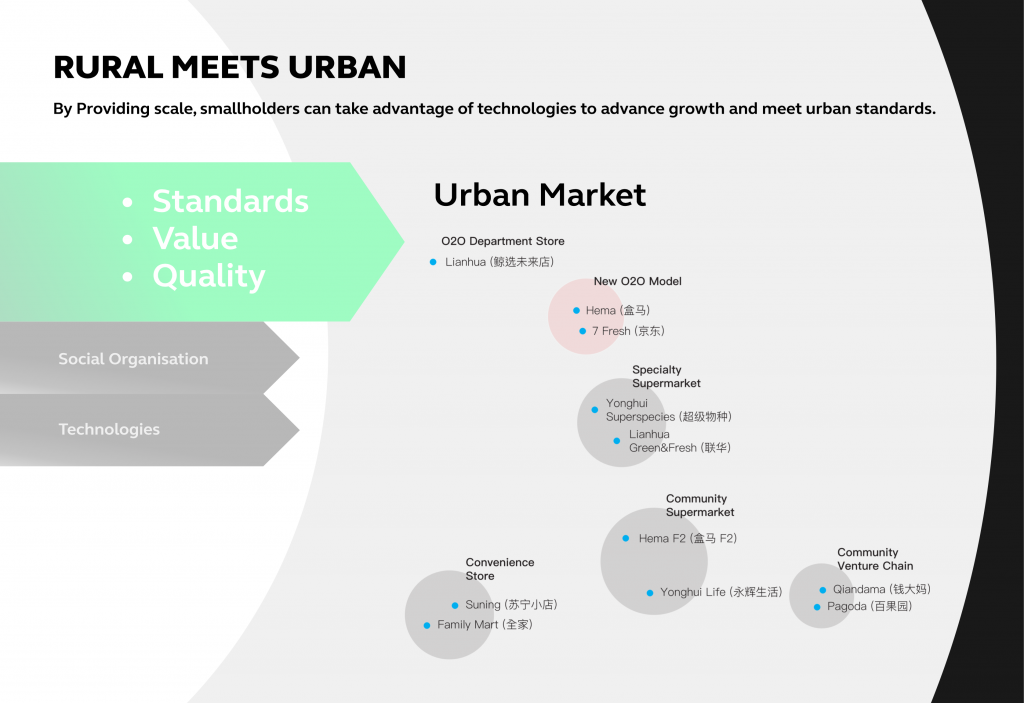

The Result: A sustainable rural-urban economy

Download full report “A new model for inclusive agriculture: The future of China’s rural development”:

Copyright of the Global Institute for Tomorrow, Hong Kong (2018).